Pushing Hands

In the rural corner of West Bengal stays a custodian of art, Madhushree Hatial working tirelessly to preserve traditional folk music and tribal art of the region. Gurbeer Singh Chawla reports

In rural communities of India, customs are highly embedded inside the community and flourish there. However, these old civilizations are frequently marginalized by modernizing society. Amidst this, some committed people work hard to protect and revitalize traditional culture. Madhushree Hatial, a folk musician and custodian of art from West Bengal is uplifting the dying art form and music to make them mainstream.

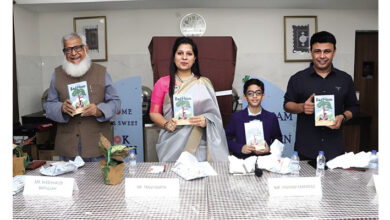

A versatile folk singer and the custodian of traditional art form from different tribal cultures of West Bengal, Odisha, and Jharkhand, Hatial is a recipient of National Award.

The 21st-century custodian of folk music and art, Hatial is a National Award-winning singer. A versatile folk singer and the custodian of traditional art form from different tribal cultures of West Bengal, Odisha, and Jharkhand, Hatial is a recipient of Indira Kirti Samman (2018), Kavi/Sahityik Samman Award (2018), and Sangeet Natak Akademi Award (2018) for promoting folk music.

Changing the tune

The founder of Maromia and Samproday Trust in Jhargram, West Bengal, Hatial has dedicated her life to preserving and documenting tribal art and empowering tribal women in Odisha, Jharkhand, and West Bengal.

While she grew up to be a musician, preserving regional art is her passion. Her ‘Jhumur’ song – a traditional folk song from Jharkhand was sung, composed and choreographed with Chhau moves by Hatial to make it contemporary and relatable for the young generation. The song earned her the Sangeet Natak Academy award in 2018. The song became an overnight hit. It secured a space in the National Museum which documents Hatial’s compositions of ‘Jhumur’ and ‘Manasa Mangal’ — a folk song from Bengal recreated by the musician. Additionally, 20 of her traditional wedding songs (Biha Geet) have been made available for scholarly study of music and art.

I hope one day indigenous arts and culture are not just honoured internationally but also maintained. I want to create educational institutions like the ancient Gurukuls and integrate traditional knowledge with contemporary technologies.”

An Assistant Professor of Folk Music at N L K Women’s College in West Bengal, Hatial also believes that folk music has a therapeutic capacity to reduce stress and mental health difficulties. She uses music as a therapy for tribal children and youngsters to promote mental health and happiness.

Down to a fine art

Hatial’s commitment to preserving traditional art goes beyond music. She also promotes visual arts and paints depicting Jharkhand’s harvest festival Sohrai, using paints made from colourful flowers, and natural brushes extracted from tree branches. Her art depicts indigenous references to animals, plants, and other natural elements that emphasize an innate connection between nature and the spirit of tribal life.

Additionally, the Trust has used abundance of Mahua and Sal trees to generate employment for women in the community. “Women use the Mahua spirit to make hand sanitisers and Mahua flower pickles as a source of revenue. The trust also organizes skill development programs which has led to a growth in the manufacture of Sal leaf plates and bowls as well” says Hatial.

Art in her genes

Hatial’s love for art comes from her father who was a passionate supporter of tribal arts and customs, during her formative years in Jhargram. It was much later when Hatial started taking a keen interest in the centuries-old local art from her region and took action when the historic tribal legacy appeared to deteriorate. “I felt the necessity to protect tribal groups’ unique cultural heritage, which was in danger of disappearing in the current digital era,” says Hatial.

I felt the necessity to protect tribal groups’ unique cultural heritage, which was in danger of disappearing in the current digital era.”

Over the years, the ‘Jhumur’ dance and Sohrai art programs have helped to preserve tribal history to a great extent. “By bringing nearly dead art traditions back to life, these projects have produced a new generation of talented folk artists. Additionally, by enabling more than a thousand tribal

women to organize self-help groups and produce traditional arts and crafts, Hatial’s trust promotes economic independence.

The big picture

In order to meet technological advancements and make local art reach the masses, Hatial developed a mobile library called ‘Bhramyaman Pathagar’ to promote traditional art and culture. The project seeks to re-establish a connection between young generation and ancient art and its history.

“I hope one day indigenous arts and culture are not just honoured internationally but also maintained. I want to create educational institutions like the ancient Gurukuls and integrate traditional knowledge with contemporary technologies,” expresses the professor and informs that her goal is to safeguard, maintain, and advance tribal art, culture, and literature to guarantee that these priceless customs live on for many more generations.