Yes, Chef!

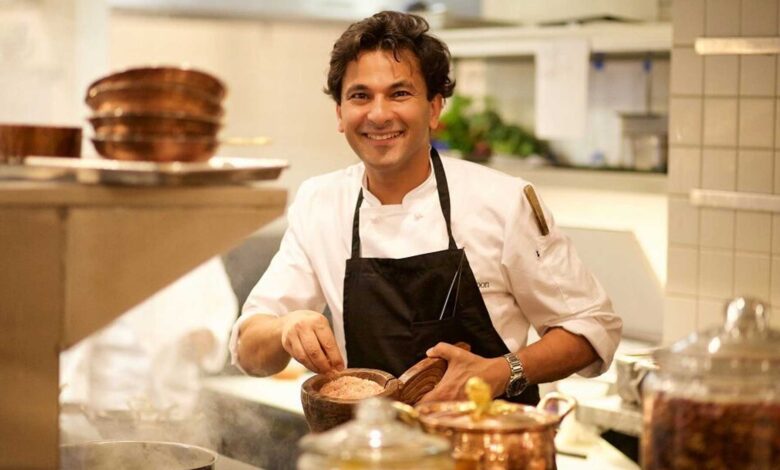

Vikas Khanna — celebrity chef, six-time-recipient of the much-coveted Michelin star for his New York-based Indian restaurant, Junoon, and now a filmmaker — indulges in a decadent conversation with Priyanka Chandani that’s rich in honesty, laden with anecdotes, peppered with humour and garnished with wholesome insights about paying it forward

Vikas Khanna, poster boy of Indian cuisine worldwide, needs no introduction. From being the first global Indian chef to have received a Michelin star six consecutive years for his New York restaurant Junoon, to whipping up delicacies for a glittering roster of the veritable Who’s who ― the Obamas, Dalai Lama and recently, Indian premier Narendra Modi in New York ― the Masterchef is a force to be reckoned with in the culinary world.

Giving Back

The Amritsar-born chef started working as a child and was running a full-time food business by the time he was 16 years old, which, according to Khanna, gave him wings to explore. The chef had this insatiable need to contribute to the community, which led him to become the goodwill ambassador of the Smile Foundation. “I believe that my life is going to undertake a trajectory after some time. Something is telling me intuitively that you know your body very well, intuitively my body says that my mind is inclining towards that,” muses the chef and hopes that he can work towards solving the malnutrition problem through his food. “Anything I do is somehow associated with food. Even the films I make are related to food, and when it is not so, I try to use my knowledge in food to make a movie or a documentary,” says the bestselling author.

Someday you must stand on your own ground to talk about Indian food and say that you can’t buy this, and that is not for sale. It comes with a price.”

Feeding India

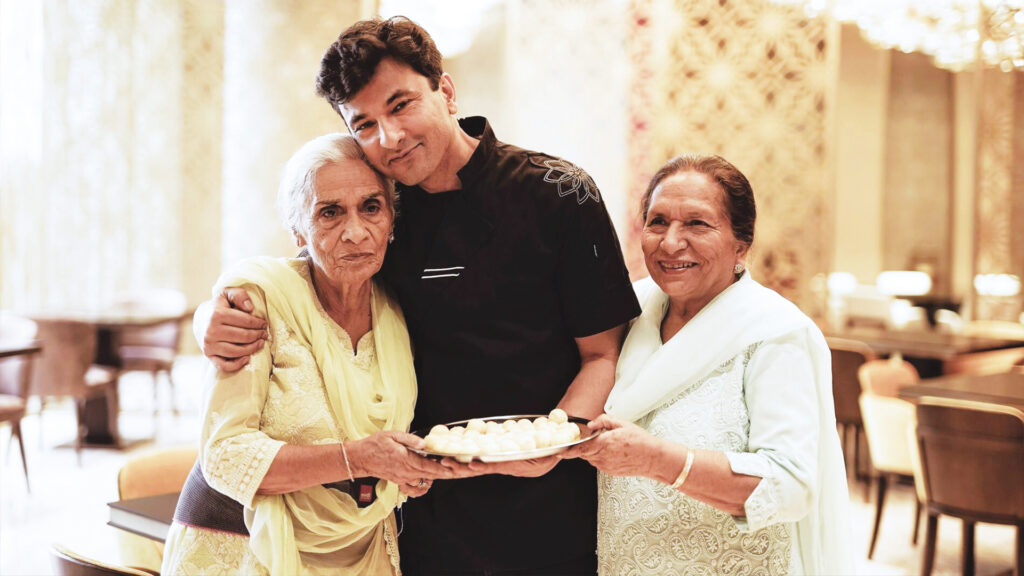

Along with his celebratory status as a chef comes his humble contributions to society. Whether it is cooking in Gurudwaras, serving food during Ramadan, or his various initiatives during the Covid-19 pandemic, Khanna takes point when it comes to giving back to society. Going back in time to the Covid-19pandemic, Khanna along with his team collected over 100 quintals of dry ration and helped families in more than 15 cities of India such as Gaziabad, Meerut, Pune, Jodhpur, Mijwan, Vrindavan, Bhopal, Mangalore, Delhi, Dharamsala, etc. It was the same time during Ramadan. Every year during Ramadan, Khanna ensures that his team distributes food that her personally cooks.

Analogies of the heart

“During that time, I saw the most beautiful face of humanity, and how willingly people go out their way to help the ones in need,” recalls Khanna. He started the entire chain of creating a food supply for so many cities in need by asking a simple question from thousands of miles away. “Would you help, please?” And the answer was always ‘yes’. The initiative ‘Feed India’ or ‘Barkat’ crossed 30 million meals following a single tweet by the chef which led to feeling millions of people in need across 135 cities in India. “My mother lives alone in Amritsar, and I thought, what if she needed help and there was no one to help her?” he says simply. Khanna has also been working with the team of the Robin Hood Army to facilitate the underprivileged and needy. Interestingly, Khanna dedicated the 30 millionth meal to Bollywood lyricist Manoj Muntashir with a patriotic song featuring Akshay Kumar.

Cooking for all

Khanna has also been promoting the concept of the community kitchen. He cooks at those kitchens for the homeless. In the aftermath of the Asian tsunami in 2004, Khanna organised a fundraiser drive called New York Chefs Cooking for Life. The momentum came from the spirituality of his growing-up years. He says, “Even though, I was born in a Hindu family, we celebrated everything in Hinduism as well as all the Sikh festivals, Eid, Christmas, Jayanti,” he shares with a child-like enthusiasm of his wonder years.

Life’s teachable moments

The chef says, it is these experiences that shaped him as a better chef, writer and a filmmaker. “When you run a restaurant, you become arrogant, and you can see that because there’s pressure in running a Michelin-star restaurant. I realized this much later. In 2013, one lady came to my restaurant, and she broke me down. She told me what I am and how they love me for what I was and not the one. That 90-yearold lady came from Toronto, and it was her first dining experience in her life. She said that her family was from Amritsar and wanted to meet me because she felt I carry that smile of her hometown since I am from Amritsar. I was rude and said I can’t go out and meet her because my kitchen is busy. It’s very difficult to run a kitchen in a restaurant.

Whether it is cooking in Gurudwaras, serving food during Ramadan, or his various initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic, Chef Khanna takes the first chef when it comes to giving back to society

The pressure is too much for a human mind when the entire America is watching you. You are too much into work and you suddenly feel defocused when someone says you are carrying the smile of their ancestors. That human interaction is the biggest example and has stayed with me. I accept my mistakes and say that I was not good. I try to be a better human being now,” confesses Khanna.

Unpredictability and integrity

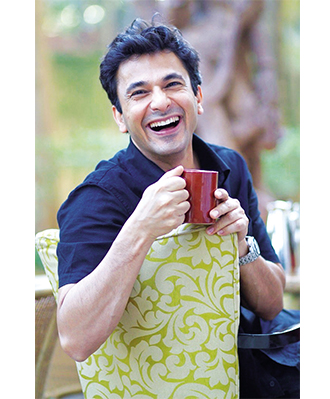

Wearing many hats can be tough, however, it is the unpredictability of his choices that keeps him motivated. “I love when people say ‘Oh! You’re so unpredictable’ and I think that’s what is important,” he says recalling that renowned British chef Gordon Ramsey also calls him unpredictable. “He tells me ‘You are so unpredictable and you get credit because you do everything at par with international quality’,” Khanna recalls, reiterating Ramsey’s words.

Whether it is about cooking, running restaurants across the world, penning books, or making movies, the chef has done everything with integrity by keeping it under wrap till it is ready for the big reveal. “This is what I believe. I keep the integrity of my work as much extent as possible,” confirms the chef and confesses that his motive to enter the food industry was never money. “I just came in because I thought it was such a representation of India’s real fabric. What India is made of is on the plate of this country,” he explains.

I make movies with a pure heart. I am not a trained filmmaker; I am a trained chef and to do something different was a tough decision.

Identity struggle

Achieving something on your own terms comes with a price and it is no different for Khanna. In the last 23 years, the chef has lived a very public life and spoken about how dark the food industry is. How hard it is for brown people or people of colour to rise without selling themselves. “Someday you have to stand on your own ground to talk about Indian food and say that you can’t buy this and this is not for sale. It comes with a price. In the western world, they see you as you can never merge with us, of course, I am going to merge with you. But I am also going to be outstanding. It takes a lot. People find difficulty in pronouncing my name and say change it or my accent is not good, but you don’t want to do that. These things happen and these are unsaid wars, very silent and under the table. I only do Indian cuisine, and this is as unapologetic as it can be,” says the chef matter-of-factly.

Global gastronomy

Talking about experimenting with Indian cuisine globally, the chef points out that it is a part of the fire. “When there’s so much attention, you can’t run away from the fact that there will be abuse. Twenty years ago, it was hard for us to sell an Indian dish. People now know Chicken Tikka and Naan. We have to make an effort to tell them about our food and make it a vocabulary. Being the guardians, we must do that to promote Indian cuisine. Yes, there will be abuse and a lot of people will be making different things but that’s fine. At a French restaurant, there’s curry ice cream. The chef told me that ‘you taught us many years ago’. It was fantastic. It is his interpretation that you can’t make firewalls and say you can’t do this. It is going to happen. It is inevitable when things become popular or relevant,” explains the chef.

One wonders if he had to make compromises while making Indian food famous on foreign land and survive? “Oh, many times! I used to hear that we make stuffed Idli filled with mushrooms and sauce. I did that. The name of the game is survival. People come after you and they abuse you but you are just trying to survive. I have done Dosa with cheese, and I am not going to walk away from what I have done.

I was also staying alive and coming to terms and saying that this is the Indian food I am going to serve with no apologies, it takes a lot of hard work and credit building. I can’t come from Amritsar to America and say this is the kanji and you have to drink it. There’s so much building that went into it before you could stand on the stage and say this is how we eat it in India, of course, we have to first survive,” says Khanna.

There are unsaid wars, very silent and under the table. I only do Indian cuisine, and this is as unapologetic as it can be!”

Behind the scenes

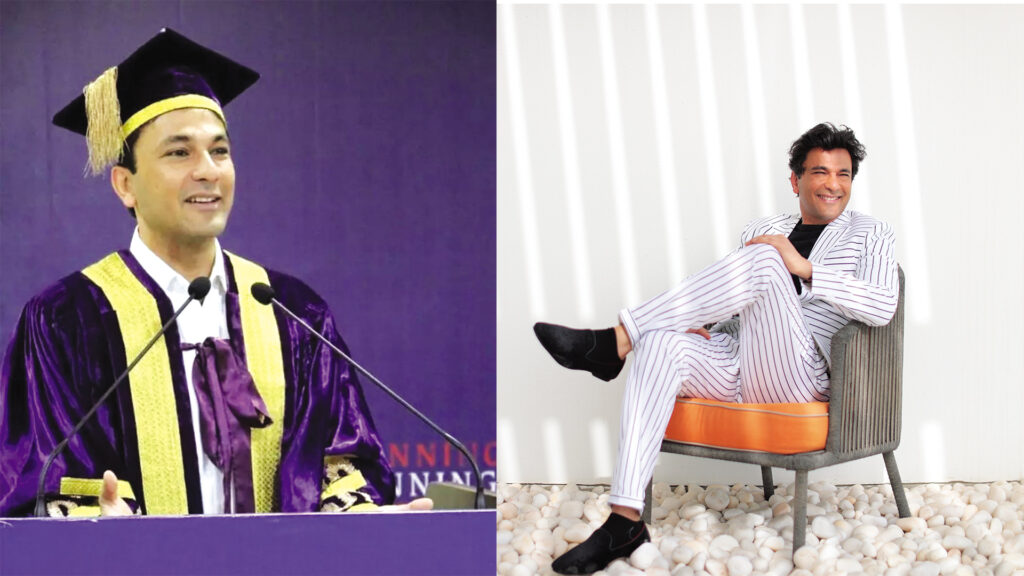

Colour me surprised when I heard that Khanna decided to step behind the camera to helm the Neena Guptastarrer The Last Colour and Shabana Azmi-led Imaginary Rain. The former film even made it to the long list of the Best Film category at the Oscars 2020. Both his films celebrate women of India. While the Last Colour celebrates resilience and women empowerment and is based on the life of widows of Vrindavan and Varanasi in India, Imaginary Rain highlights the woman force behind every successful man.

Interestingly, both the films are adaptations of books with the same names authored by Khanna himself. “I make movies with a pure heart. I am not a trained filmmaker, I am a trained chef and to do something different was a tough decision,” says the filmmaker and feels that it is because of the story of empowerment, inclusively and society’s need to change to bring that real self-identity in India has attracted the international audience.

Guilt as motivation With all his achievements, Khanna confesses that it is not many accolades that keep him going but it is his guilt that helped him survived in America. “The guilt of leaving my mother and making sure that she is proud of whatever India I was representing. Making sure that she doesn’t get the pressure of what I was going through. You want to give her the face that I am doing it for you, so you sacrifice the most in this biggest equation. I am the biggest loser in this game. She lost the most when her young son walked out of the house to create a life for himself. That guilt keeps me going for every project that I take up. I feel guilty for not being with my father when he died. I should have understood my father. I should have asked him what he wanted. I accept that privileges were given to me because there was much more responsibility that came with it and I ran away from it,” confesses the filmmaker.

While Khanna lives in New York and hails from Amritsar, he calls Varanasi his home. “I love being in Varanasi because no other city gave me that comfort. Most of my projects have happened in Varanasi. Amritsar is precious to me but every time I am broken or bankrupt, I have gone to Varanasi for inspiration,” says Khanna as we sign off.